Organization Design

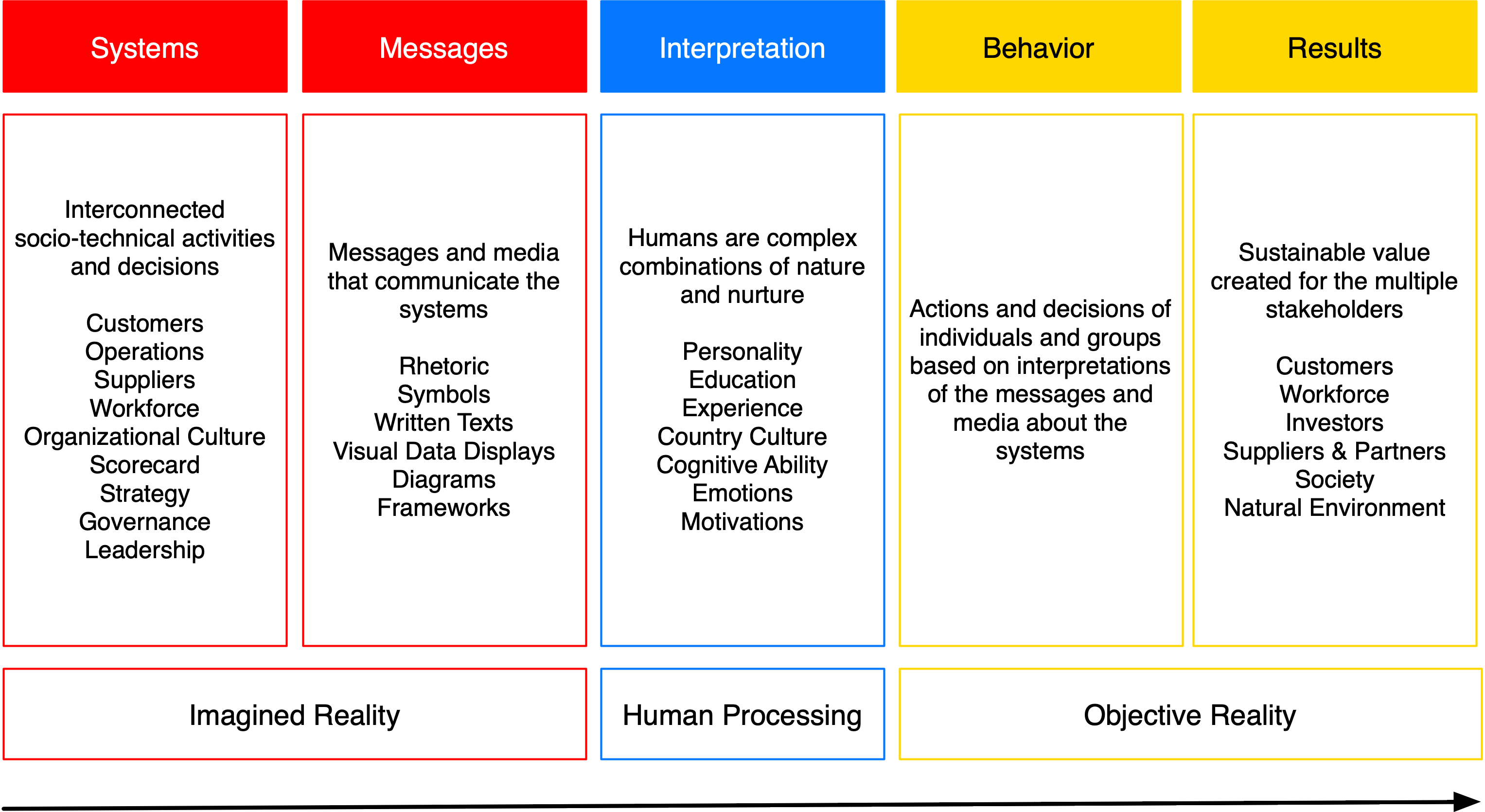

Organizations are complex, socio-technical systems designed to accomplish specific purposes and goals. They are imagined realities that exist in the minds of the people involved. That imagined reality includes explicit knowledge of how to accomplish the activities and make informed decisions, as well as the connections to other activities and decisions throughout the organization. These methods are communicated to people within the organization through a collection of formal and informal messages and media, which are interpreted by individuals based on their personality, education, cognitive abilities, and other factors. Guided by their thoughts and feelings about these messages, people undertake activities and make decisions to achieve the desired results and implement the strategy, thus creating the objective reality. It is their actions and decisions that produce the sustainable value for the multiple stakeholders.

Organization Design

Systems

There are three levels of systems relevant to organizations: the individual, the organizational, and the societal. At the individual level, systems represent the explicit knowledge of how to accomplish activities and make decisions effectively throughout the organization. Organizations are composed of a wide variety of activities, including understanding customers, designing and developing products, planning, managing operations, evaluating and improving the supply chain, developing and engaging the workforce, measuring and analyzing performance, and developing and deploying strategies, among others. Systematic methods for individual activities are explicit, repeatable, and thus teachable to a large number of people. This is not a new idea; Chinese philosopher Mo-Tze (a.k.a. Micius) proposed a systems approach to governing large numbers of people approximately 500 B.C.E.

“Whoever pursues a business in this world must have a system. A business which has attained success without a system does not exist. From ministers and generals down to the hundreds of craftsmen, every one of them has a system. The craftsmen employ the ruler to make a square and the compass to make a circle. All of them, both skilled and unskilled, use this system. The skilled may at times accomplish a circle and a square by their own dexterity. But with a system, even the unskilled may achieve the same result, though dexterity they have none. Hence, every craftsman possesses a system as a model. Now, if we govern the empire, or a large state, without a system as a model, are we not even less intelligent than a common craftsman?” (Wu, 1928, p. 226)

At the organizational level, the activities and decisions are connected and interdependent. Organizational systems facilitate the cooperation and coordination of the various activities to accomplish the overall firm's results and outcomes. A variety of devices are used to align the efforts of people throughout the organization, including concepts, goals, and guidelines. When well-designed, they encourage and facilitate the coordinated cross-functional activities and decisions of large numbers of humans toward common goals and objectives.

Unfortunately, in our efforts to create predictable results, organization designers have often created systems that are slow, cumbersome, and overly rigid, with unnecessary constraints, resulting in predictably poor performance. So prevalent are these poor designs that many people can’t imagine systems being effective in today’s modern, dynamic, and uncertain environment. Fortunately, systems can be designed to properly fit and enhance a wide variety of activities and contexts, including those that require flexibility, creativity, custom solutions, and agility, as well as those that need strict compliance for safety and quality results. The trick is to understand the nature of the activities and decisions being designed.

The definition of “systematic” varies depending on the nature of the system being designed, including the degree to which the work is predictable vs. ambiguous and the level of human involvement (Repenning et al., 2018). If the work is controllable and outputs are predictable, such as manufacturing physical products, then a high level of structure and standardization is appropriate. If, on the other hand, the work is creative and ambiguous, such as strategy development or product design and development, a less structured and more collaborative approach, utilizing flexible tools and techniques, is appropriate. Well-designed systems incorporate the optimal amount and type of structure to facilitate effective performance while avoiding the addition of unnecessary constraints.

High-performing systems are explicitly defined, aligned, integrated, and continuously evolving. Systematic methods are explicit and repeatable knowledge on how best to do a particular activity or make a decision. Consequently, it is shareable, teachable, and thus scalable. And, it can be measured, proactively managed, evaluated, and improved (Latham & Vinyard, 2011, p. 625). Well-designed systematic methods are aligned with critical aspects of the organization’s unique context, including its strategy, organizational culture, regulatory environment, workforce capabilities, and other relevant factors. They are integrated with other appropriate systems to enable coordinated actions across the organization, forming a coherent and interconnected enterprise. And, they continually evolve to improve performance and remain relevant in a rapidly changing world.

The societal level defines the operating environments that the organization must navigate to accomplish its objectives, including political, economic, social (including country culture), technological, legal, natural, and competitive environments. These are complex, interdependent combinations of a wide variety of countries, institutions, organizations, and relationships. These societal systems seldom have a central designer or manager. Instead, they often evolve through a variety of policies and strategies carried out independently by the individual parties involved. For example, the 2008 financial crisis was caused by the uncoordinated activities and decisions of various players attempting to optimize their results (Latham, 2009). While societal-level systems are typically outside the control of organizational leaders, effective organizational-level design requires an understanding and consideration of the larger system and the organization’s role within it.

It is not enough to come up with a systematic, aligned, integrated, and evolving approach; it must also be communicated effectively to the people involved in the activities and those making the decisions. To be effective, the design must be both technically effective for the activities and decisions and compelling to humans.

Messages

Systems are communicated through a variety of formal and informal messages and media, including observations of what other people say and do. These various verbal and visual inputs inform how to perform the activities and make decisions throughout the organization.

Think about a typical day in your organization. As you work, you are exposed to numerous inputs from various sources. You have instructions on how to perform your job, including work instructions, policies, and digital systems designed to facilitate your work. You have metrics that provide feedback as to how well you are doing your job. Then, during a video conference call, your boss outlines specific expectations, priorities, feedback, and advice. After that, you text with a coworker who shares their views on how to succeed, along with the latest gossip. “Did you hear who is getting promoted?” You then receive an email outlining the incentive system and bonus structure, including the relevant criteria and measurements. Embedded in these messages are some of the norms, values, and expectations of the organization as well as new and emerging directions and practices. Messages and media can be divided into two categories: verbal (what people hear) and visual (what people see).

Verbal messages or rhetoric are essential to managerial judgement and communicating how to accomplish activities and make decisions throughout the organization. Rhetoric is not only a technical explanation but also a form of persuasion, a necessary part of deploying new organizational designs, which includes appealing to reason, credibility, and emotion (Spender, 1989). These messages can be purposefully designed to achieve the desired behaviors.

Messages are also visual symbols transmitted, including text documents, numbers, visual displays of quantitative data, diagrams, and the actions of others. Well-designed visuals reduce cognitive load by simplifying complex data, enabling decision-makers to process information more efficiently and accurately. Visual displays can support both intuitive, fast decision-making and slower, detailed analysis (Kahneman, 2011).

All too often, the messages are conflicting, leaving individuals to decide for themselves which to follow. To be effective, the messages and media that communicate the approaches must be aligned with the desired behaviors, consistent with each other, and create a clear and accurate picture in the minds of the people.

Ultimately, organizational design encompasses all the information that people see and hear that influences their behavior. The task of the organization designer is to design approaches, along with the messages and media, that convey the approach to the people for their interpretation and action. To do that effectively requires a thorough understanding of the people involved.

Interpretation

Between the imagined reality and the objective reality are humans who interpret the messages and decide what to do and say. The effectiveness of a design is determined by how well the interpretation of the design and resulting behavior match the original intent. People are complex combinations of nature and nurture, including personality, education, experience, cultural background, cognitive ability, emotions, and motivations (Pinker, 2002). Consequently, people interpret what they see and hear in the organization differently.

There are many examples of imagined realities that didn’t work. Why? Humans are not completely malleable and often reject or undermine our imagined reality, and some imagined realities are counter to human nature. To create effective approaches and messages that achieve our objectives, we must understand what it is like to be the people we are designing for, and how they think and feel. This requires information about their preferences from those individuals directly and scientific knowledge about them that they may not even be aware of.

Personality traits, including openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, are both inherited and acquired through learning (Power and Pluess, 2015). Personality influences the fit for culture and work activities, as well as the ability to adapt to change.

Formal education and informal learning shape how and what people think about what they see and hear. Learning influences an individual's cognitive abilities, problem-solving strategies, and ability to acquire new knowledge. Education also shapes an individual's values and perspectives, which, in turn, influence their attitudes toward work, ethics, and social responsibility within an organization.

Experience provides practical understanding and skills that education alone cannot.

Experienced employees often possess valuable tacit knowledge that facilitates efficient problem-solving and decision-making, and they tend to have a deeper understanding of organizational norms, politics, and processes, enabling them to navigate the workplace more effectively.

Country culture, including values, symbols, heroes, and practices, influences how people perceive the world and interact with one another, including leadership styles, organizational policies, and processes (Hofstede et al., 2010). For example, in high-power distance cultures, employees may expect a more hierarchical structure and defer to authority. In contrast, in low-power distance cultures, employees prefer a more egalitarian and participatory environment.

Cognitive abilities, including reasoning, problem-solving, learning, memory, attention, and decision-making, influence how individuals perceive and interpret the information they encounter. Cognitive abilities influence an individual's capacity for innovation, strategic thinking, and problem-solving. Employees with higher cognitive ability tend to learn new tasks and information more quickly, adapt to changing work environments, and solve complex problems more effectively. Ideally, organization design helps simplify activities and decision-making (Simon, 1969).

Emotions profoundly affect attitudes, decisions, and behaviors at work. Emotions can lead to increased creativity, cooperation, job satisfaction, and a willingness to go beyond formal job duties, as well as stress, burnout, reduced productivity, conflict, and withdrawal behaviors. Different ways of presenting messages about the approaches evoke different emotions, which in turn influence behavior.

Motivations are the internal and external forces that drive an individual to initiate, direct, and sustain goal-oriented behaviors. They explain why people behave in specific ways. Motivation is influenced by various messages that describe the desired behavior, including policies, incentives, leader feedback, and peer approval and disapproval. Motivated employees are typically more engaged, productive, committed, and adaptable.

We inherit many characteristics and abilities from our ancestors, and the evidence continues to accumulate regarding the extent to which these traits are inherited versus acquired through learning. While we understand a great deal about human behavior in aggregate, given the variation among individuals, understanding each person remains a challenge.

When you combine a diverse group of individuals to form an organization, the potential permutations of social interactions become even more complex. Not only do individuals interpret the approaches and messages differently, but they also influence each other’s interpretations. Ultimately, how they think and feel about the messages affects their behavior, what they say, and do.

Behavior

What people say and do is observable and measurable, and thus can be used to determine the effectiveness of the designs. The measurement of behavioral indicators and performance metrics helps us test how well our designs are working (Tantia, 2017). These objective results, along with the behaviors that led to them, will validate our designs or provide us with the necessary information to adjust and try again.

Organizations require individuals who cannot only execute activities and make decisions aligned with their overall purpose and objectives but also collaborate effectively to deliver the desired value to stakeholders. While many propose lists of desired behaviors, such as commitment, teamwork, integrity, and trust, each organization gets to decide for itself what behaviors it needs to create the objective reality it desires.

The behaviors you observe in an organization tell you how they interpret the systems and messages. If there is a mismatch between the desired and observed behavior, then either the system needs to be adjusted or the messages and media need to be revised and then retested until the behavior matches your intent.

Organization design is a learning process that involves discovering what works, what doesn’t, and under what conditions. While the perfect design might be unattainable, we can become increasingly accurate over time, thereby increasing the chances of creating the value we desire. What people think and feel about the approaches and messages influences what they say and do, and that behavior produces the results.

Results

Organizations are intended to be rational enterprises designed to achieve specific outcomes or objective reality. We have known for a long time that investors do not create wealth on their own; instead, people within the organization create value for customers who are willing to pay more for the products and services than it costs to produce them, providing a return on the owners’ investment (Simon, 1997). A quick thought experiment reveals the interdependence of these three groups. If one of the three groups is unsuccessful and decides to withdraw from the arrangement, the value produced for all three groups collapses.

Many organizations also rely on the performance of suppliers and partners to create value for their customers. While some organizations adopt a short-term, transactional approach to suppliers, others have found that mutually beneficial arrangements can be designed to enable suppliers to improve and create even greater value for the organization. Deming (1986) proposed ending the practice of awarding contracts to suppliers based solely on price and instead adopting a strategy that considers total cost, fosters long-term relationships, promotes supplier development, and shares responsibility.

Since then, the scope of organizational responsibility expanded further to include society (Freeman et al., 2010). Some organizations have recognized that their success depends on society providing an educated and healthy workforce, the rule of law, and an economic environment with consumers who can afford to purchase products and services. Organizations employ people who then spend money to buy goods and services from other organizations, creating a flow of wealth that drives economic growth.

Finally, the natural environment has emerged as a key stakeholder that impacts our ability to create wealth today and in the future. The empirical evidence continues to support the conclusion that the economic and social costs of climate change will be more expensive than the cost of taking action now (IPCC, 2023). Ultimately, the organization design challenge is, as the United Nations proposed in 1987, “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Each organization's leaders must choose which stakeholders they will serve and how; of course, they must then live with the consequences. Creating sustainable profits requires that this interdependent system of investors, workforce, customers, suppliers, society, and the natural environment be designed to create value for all six groups, both current and future. Consequently, resilient organizations try to minimize trade-offs and instead focus on developing ever-evolving designs that create sustainable value for multiple stakeholders.

References

IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 184 pp., https://doi.org/10.59327/ipcc/ar6-9789291691647

Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, H., Jeffrey S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Latham, J. R. (2009). Complex system design: Creating sustainable change in the mortgage-finance system. Quality Management Journal 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2009.11918235

Latham, J. R., & Vinyard, J. (2011). Organization diagnosis, design and transformation: A Baldrige User’s Guide (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. https://drjohnlatham.com/books/organization-diagnosis-design-and-transformation/

Pinker, S. (2002). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. Viking.

Power, R. A., & Pluess, M. (2015). Heritability estimates of the Big Five personality traits based on common genetic variants. Translational Psychiatry, 5(7), e604 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.96

Repenning, N. P., Kieffer, D., & Repenning, J. (2018). A new approach to designing work. Sloan Management Review, 59(2).

Simon, H. A. (1997). Administrative Behavior, 4th Edition (4th ed). Free Press.

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. The M.I.T. Press.

Spender, J.-C. (1989). Industry recipes: An enquiry into the nature and sources of managerial judgement. Basil Blackwell Ltd.

Tantia, P. (2017). The new science of designing for humans. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 15, 29-33. https://doi.org/10.48558/K1RX-Z412

United Nations. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: Brundtland report [Report]. United Nations General Assembly.

Wu, K.-C. (1928). Ancient Chinese political theories. The Commercial Press, Limited.