The Studio

Why a studio? Leaders today face many challenges that require designing or redesigning organizational activities and decisions to achieve and sustain high performance. While best practices from other companies, consultants, and business books may be effective, they seldom yield the high-performance levels achievable with a custom “bespoke” solution. What is needed is a flexible methodology and framework, along with a space to reimagine the organization.

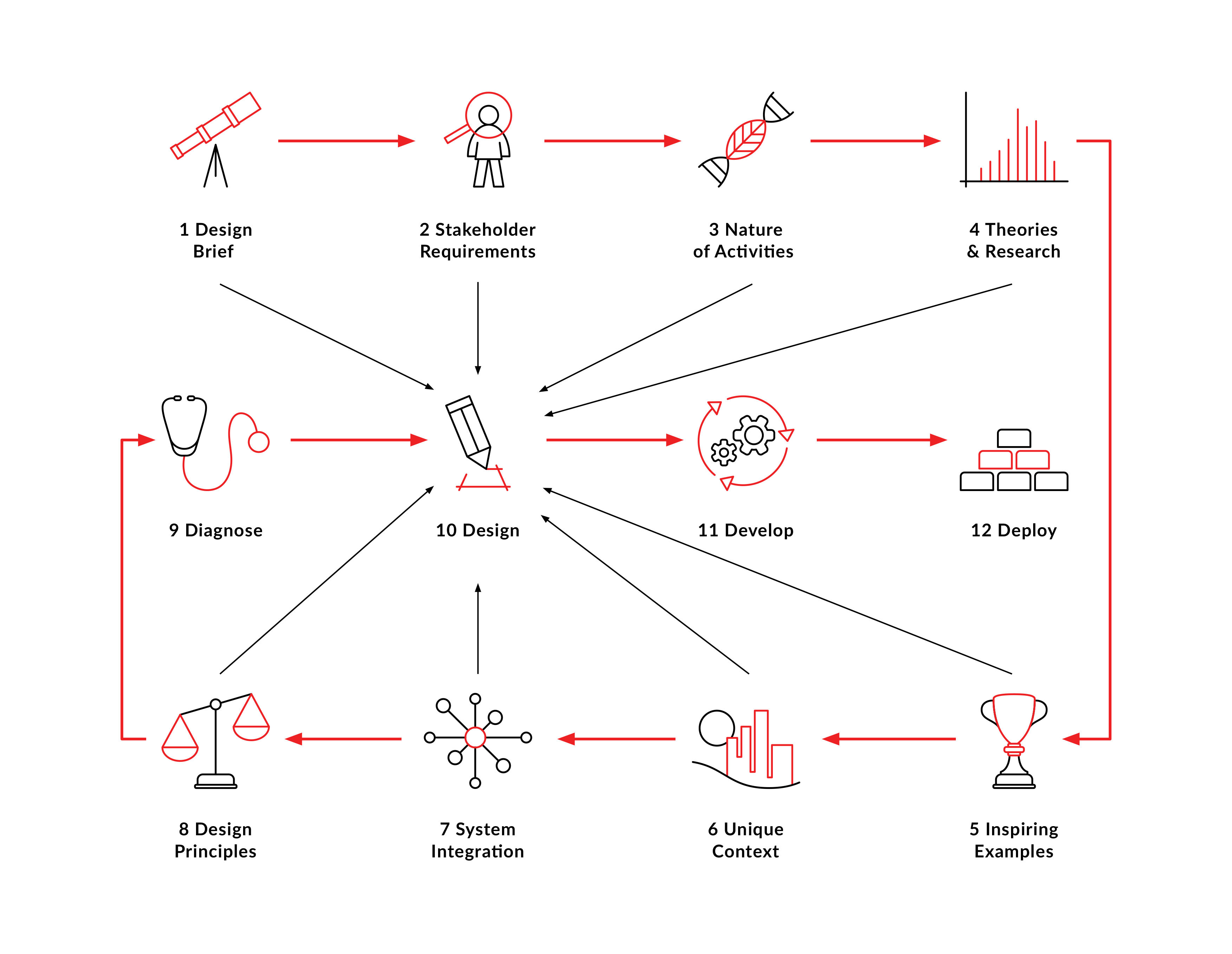

Originating from the Latin word “studium,” meaning to study, the Italian word “studio” means a place to study or work. Organization Design Studio® is a virtual space for analyzing organizations and learning through hands-on design practice. It is a place to work on the organization, rather than working in it. The studio includes 12 labs that guide the inquiry and innovation needed for custom designs (Latham, 2012).

Design Methodology and Framework

Beginning with the purpose, the studio is human-centered, addressing the stakeholders’ requirements and the nature of the activities and decisions being designed. The labs combine the best of academia and practice using empirical evidence and inspiring examples to inform the design process. The real power in organizational design lies in aligning the activities and decisions with the unique organizational context and integrating them with other relevant activities and decision-making processes.

Based on these inputs and selected design principles, the existing system is evaluated to identify characteristics that should be retained and those that require redesign. The studio approach then combines critical analysis with creativity to design, develop, and deploy your new system. Organizational systems are never complete; they require continuous evaluation and improvement to remain relevant in an ever-changing world. Our labs offer a “learn by doing” experience, where you build your design skills by creating a custom system tailored to your organization's specific needs.

1. Design Brief

Organization design is a rational, purpose-driven process that enables the achievement of specific objectives and results. The first step in the design brief is to identify the leaders’ intent - the WHY. What are the purposes of the system being designed? What are the expected benefits? Based on the purpose, determine the project's scope. WHAT is included and what is excluded? What activities and decisions will be part of the systematic approach? Which parts of the organization will be involved in this system? Then identify WHO will be included on the design team. When it comes to design, if two people think alike, one of them is unnecessary. The design team ideally consists of diverse perspectives that address key aspects of the scope and relevant aspects of the larger organizational system. Then, develop a project management plan outlining HOW, WHEN, and WHERE the design team will accomplish the design activities. These four components are explicitly defined in a formal document that can be shared and revised as the project unfolds.

1.1 Leadership Intent - WHY - Identify and understand the external and internal forces for change. What is motivating the design or redesign of a system? Identify the purposes and expected benefits of the new system.

1.2 Project Scope - WHAT - Identify the activities and decisions included and which are excluded? Identify which parts of the organization will be included, such as departments and functions (breadth) and the organizational levels (depth).

1.3 Design Team - WHO - Identify and select the participants that will comprise the core design team. Base the team composition on a mix of organizational experience, technical knowledge, and country-specific cultural experience and knowledge, as well as diverse demographic perspectives.

1.4 Project Plan - HOW, WHEN, and WHERE - Develop a design project plan following the remaining 11 design labs, including a schedule and locations for the activities.

2. Stakeholder Requirements

Long-term value creation requires a deep understanding of the individuals involved in the activities and impacted by the results. This stakeholder-centered approach begins with the three core stakeholders: investors (the funding source), customers (the beneficiaries of the solutions), and those who work to create the solutions (the workforce). These three groups are interdependent, and each cannot succeed without the success of the other two. Suppliers and partners (both external and internal) can also be essential considerations, as they are integral to the success of creating and delivering the outputs of the designed approach. Finally, society and the natural environment are often crucial considerations in the design of organizational activities and decisions. Once you have identified the relevant stakeholders for the system being designed, the task is to determine their specific requirements. Those are the requirements that the approach being designed must meet. The stakeholder lab tools and techniques help you explore multiple stakeholders, identify their requirements, and determine for yourself which stakeholders and requirements will be addressed by your design.

2.1 Identified and Categorized - Identify the key stakeholder groups and sub-groups applicable to the system being designed, and categorize each group based on their relationship to the system being designed, including involved, impacted, and influencer.

2.2 Requirements - Identify the requirements for each stakeholder group based on existing sources and listening methods.

2.3 Empathy Profiles - Understand what it is like to be a member of each group - develop an empathy profile for a key stakeholder group, including what they see and hear, think and feel, and say and do.

3. Nature of Activities

Organizational approaches are interconnected combinations of physical, digital, and human components that make up the inputs, activities, decisions, and outputs. These socio-technical systematic approaches range from predictable physical activities to complex decision making to ambiguous creative activities. The nature of the activities influences the amount and type of structure, the level of control, and the level of task specificity that is appropriate for the design. Physical activities such as manufacturing and transportation involve materials that adhere to immutable natural laws and often require a high degree of standardization and focus on conformance to minimize variation. Decisions such as loan processing and insurance claims provide the decision-makers with the necessary and accurate information, decision criteria, and tools. Creative approaches, such as strategy development and product design, require a flexible structure, as they tend to be less effective when the degree of process specificity and standardization is high. The challenge in designing any system is to identify the optimal balance of structure and flexibility; just enough structure to facilitate the activity or decision without unnecessarily constraining it.

3.1 Natures Identified - Understand the physical, digital, and human natures of the system. Identify the applicable categories of activities and decisions, including physical, informational, creative, and bespoke (custom) aspects, as well as the level of human participation for each.

3.2 Optimum Structure - Identify the implications of the socio-technical mix of natures for the amount and type of structure that is appropriate for the system being designed.

4. Theories and Research

Theories are our current best explanations of how our policies and practices influence people’s behavior and, in turn, create the desired results. As the German-American psychologist Kurt Lewin proposed, "there is nothing more practical than a good theory.” Research findings provide the details of what works, what doesn’t, and under what conditions. Unfortunately, practitioners’ actions and practices are often not based on the latest scientific theories and sometimes involve practices that we already know do not work. It is unclear how modern management arrived at this point. It is hard to imagine a building architect not considering necessary scientific evidence (e.g., metallurgy) when designing a new building. Social science research has several limitations, including the limited generalizability of its findings across various contexts. Consequently, we utilize the best from academia to inform our designs, thereby increasing our chances of success while avoiding unnecessary constraints on our innovative designs. In short, when used wisely, theories and research can enhance our designs and the speed at which we arrive at a workable and effective design.

4.1 Concepts and Relationships - Identify the relevant theories and concepts, including the key variables and their relationships, the current best explanations for how the system works, and the implications for the design of the system.

4.2 Research Findings - Identify the most recent research and empirical evidence regarding the system and the implications for the design of the system. Include how the findings vary depending on the context and other factors.

5. Inspiring Examples

To incorporate the best from practice, designers must understand how others have designed their systems, drawing inspiration needed to adapt ideas and concepts creatively. The trick is to use examples to inspire creativity rather than as “best practices” to copy. In this step, the design team reviews and explores how high-performing organizations have designed similar systems for their organizations. The best designers recognize that some of the greatest insights and creative inspirations can be found in examples outside their industry and country context. Examples are useful at two different points in the design process. First, high-level conceptual design examples are helpful during the initial conceptual design process. Second, detailed examples are used during the detailed design to provide tangible options and ideas for specific system activities. Studying and creatively adapting key characteristics from example designs as part of a design thinking process can help you leap beyond the competition.

5.1 Individual Examples - Identify high-performing examples from a variety of contexts (industries, countries, etc.). Study the components of the example systems and identify the characteristics to inspire your design.

5.2 Themes - Identify common themes, outliers, and anomalies among the example systems. Combine various characteristics to form new combinations.

6. Unique Context

Designing custom systems aligned with the organization’s unique context requires understanding its internal organizational characteristics and external operating environment, including relevant country cultures. For example, the appropriate strategic management system for a local, single-location, family-owned grocery store in Italy will likely differ from that for a large multinational company with over 30,000 employees and operations in more than 40 countries. The internal context factors include the products and services, operations and locations, workforce characteristics, organizational culture (values, symbols, heroes, practices, etc.), strategy, governance model, and leadership approach. The external operating environment includes customers, suppliers, as well as the political, economic, social, technological, legal, natural, and competitive environments. In addition, the country's culture, including that of the workforce, customers, and suppliers, will influence the effectiveness of the design choices related to policies, practices, and products. Understanding what is relevant and important to the organization helps design systems that are aligned and consistent with the unique context.

6.1 Internal Context - Identify the organizational internal context factors relevant to the system being designed. Include multiple organizational dimensions that are applicable, such as products and services, operations, workforce, organizational culture, scorecard, strategy, governance, and leadership.

6.2 External Context - Identify the external operating environment factors relevant to the system being designed, including customers, suppliers, and the political, economic, societal, technological, legal, natural, and competition environments, and applicable country cultures.

7. System Integration

Changes are often made in one part of the organization with little understanding of how those changes impact other activities and decisions. To be effective, the system must be integrated with other relevant systems to provide coherent and coordinated flows of value throughout the organization. For example, a strategy system interacts with several systems, including customer knowledge and product design, operations planning, workforce capability and capacity planning, work placement decisions (such as supplier selection and management), organizational scorecard, and governance. Once the design team understands which systems are connected to the one being designed, they can identify the key inputs, outputs, and points of contact for the other systems. Designing well-integrated systems is a collaborative approach requiring the involvement of those in charge of both sides of the interface points. This systems perspective allows designers to look beyond a particular system’s immediate goal or desired outcome and identify key leverage points in the overall system to achieve their objectives and purposes.

7.1 Connected Systems - Identify the connections to other internal and external organizational and managerial systems that are relevant to the system being designed.

7.2 Inputs and Outputs - For each connected system, identify external inputs and outputs to the system along with the point of contact (process owner).

8. Design Principles

What is good design? What characteristics of systematic activities, decisions, and their arrangement contribute to meeting the needs of the multiple stakeholders? We use design principles to describe the desired characteristics of the new system. These principles guide design team decisions throughout the diagnosis, design, development, and deployment phases. The team begins with established design principles that have proven helpful in developing high-performing organizational systems, including human, efficient, agile, balanced, fact-based, convenient, congruent, coordinated, adaptable, and sustainable, to name just a few. Once the team understands the principles, they can then decide which are relevant and identify additional principles to help guide their project. Ultimately, the objective is for the design team to develop their definition of good design for the particular system being designed.

8.1 Selected Principles - Understand and select the desired design principles, and then identify how each principle will inform and influence the system currently being designed.

9. Diagnosis

If you are redesigning an existing system, in many cases, you will want to retain and build upon its strengths while addressing its weaknesses. Assessing custom-designed approaches requires a detailed understanding of the existing system and the artifacts produced during the preceding eight design activities. To evaluate the current design, the team will explore several assessment questions.

- How well does the current design address the purpose, expected benefits, and stakeholder requirements?

- How well does the current design's structure (amount and type) reflect the nature of the activities and decisions?

- How well does the current design reflect the relevant theories and research and incorporate characteristics from high-performing examples?

- How well does the current design reflect and align with the organizational context and culture?

- How well-integrated is the current design with the other systems within and outside the organization?

- How well does the current design incorporate the applicable design principles?

From these questions, the team identifies both the strengths and opportunities for improvement while avoiding the identification of specific solutions. The team then describes the rationale for each opportunity for improvement and resources to help them address the opportunity during the design lab.

9.1 Assessment - Assess the current system using comprehensive criteria questions and identify both strengths to retain and opportunities for redesign.

9.2 Rationale and Resources - Identify how each opportunity limits the organization’s ability to do something meaningful to its success, and the resources (research and examples) to help address the opportunity during the design phase.

10. Design

Using the information and concepts from the first nine activities as a “springboard,” the design team creates an ideal conceptual design, a feasible conceptual design, and then a detailed design. First, the design team stretches their thinking to develop a vision of how the organizational system could work in an ideal world with few constraints, such as unlimited resources, technology, and the desired organizational culture. When attempting to redesign an approach, design teams are often “prisoners” of their previous experiences and learning. Experience suggests that if participants first develop an ideal design with few constraints and then refine it to a feasible design that addresses the constraints, they will end up with a better design than if they proceed directly to the feasible design. The feasible design addresses the real-world constraints, obstacles, and challenges. The team then develops the descriptions and sequencing of the activities, as well as the decision criteria and relevant tools, techniques, and technologies. The detailed design is ready when it includes enough information to build a prototype.

10.1 Conceptual Design - Create an ideal conceptual design based on unlimited resources, technology, and the ideal workforce and culture, then create a feasible conceptual design that addresses the constraints.

10.2 Detailed Design - Solicit stakeholder feedback on the conceptual design and use it to create a detailed design that is ready for development and testing.

11. Develop

A detailed design is an untested hypothesis. Before it can be deployed in the organization, it must be developed using an iterative testing, refinement, and validation process. The development phase begins with a paper (or digital) prototype, followed by a pilot test of a working prototype. The first and least expensive step is to develop a paper prototype, typically consisting of flip-chart pages posted on the walls of the design studio. For virtual teams, a digital version of the prototype is also an option. The paper prototype is used to visualize the system and get feedback from the relevant stakeholders, including the integration point process owners. Involving the integration point process owners in the development helps smooth the inevitable rough patches before deployment. The next step is to develop, test, and refine a working process that incorporates all the necessary tools, techniques, technologies (T3), and decision criteria. This pilot test allows the design team to learn from the limited deployment and refine the design before full implementation. Once the new system is tested and refined, it is ready for full-scale deployment.

11.1 Prototype - Develop a “paper” (or digital) prototype of the design and conduct a “tabletop” assessment of the prototype.

11.2 Pilot Project - Test, refine, and validate the design. Identify what works and what doesn’t, then refine the design to get the system ready for deployment.

12. Deploy

Deploying a new or redesigned system throughout the appropriate parts of the organization is an exercise in leading change. The successful implementation of a new design requires a well-planned approach, trained employees, sufficient resources, and a systematic process for reviewing and managing progress. The first step is to plan the implementation, including key activities, a timeline, and the resources required. The workforce cannot execute the new or redesigned process unless they understand how it works. A communication and training plan is needed to prepare those directly involved with the new approach. Note – the more intuitive the design, the easier it is to execute, and the less training is required. As the system is deployed in different parts of the organization, the team continues to test and adapt the system to new contexts; organizational design is an ongoing process. High-performing systems and processes incorporate learning loops to ensure continuous innovation and improvement of the new system, as well as to keep it current with evolving stakeholder needs.

Today’s dynamic and unpredictable environment requires continuous design and redesign to remain relevant and successful. While presented as a sequence of activities, the studio approach is flexible and can be used in part or its entirety, depending on your specific needs. While most designs will benefit from all 12 labs, some redesigns may only need a few of the design framework activities to provide the necessary information to fix a specific issue. Once you have mastered the studio approach, you will be able to use it to meet your particular needs.

12.1 Deployment Plan - Develop a comprehensive plan that outlines the deliverables, timeline, and necessary resources, and prepare the team for the new system.

12.2 Project Management - Deploy the system to all applicable areas in the organization and actively manage the schedule, scope, cost, and performance of the system. Validate the system in each new part of the organization and evolve the system to fit the unique aspects of the various parts of the organization.

References

Latham, J. R. (2012). Management system design for sustainable excellence: Framework, practices and considerations. In Quality Management Journal 19(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2012.11918342